Epic Failures of Communication

When we look at the communication of Jesus, do we see epic failures? No, of course not. Do we see epic failures in the efforts of John the Baptist, Peter and Paul? Not there, either.

Why am I asking those questions? Because if you hold a certain belief, it sure seems like they failed. I’m talking about the belief that unbelievers will suffer eternal conscious torment. If these great evangelists intended to express the notion that unbelievers are destined to suffer eternal conscious torment, they did a really poor job of expressing it.

With this essay, I will question something that you might have believed your whole life. Many Christians believe that unbelievers will be cast in hell and will exist eternally in a state that is totally devoid of God’s presence. Some have depicted this state as one of burning, or of torment, or of intense cold, or of darkness. Regardless of the specifics, though, surely any existence that is totally devoid of God’s goodness would be a terrible one.

I believe in the existence of hell, but I believe that hell will be a place of annihilation. Those thrown into hell will eventually cease to exist and will be eternally deprived of the opportunity to live in the glorious presence of God. This is what John the Baptist, Jesus, Peter and Paul taught. They made it clear.

Many will disagree with me on that point. They believe that these men went through their lives, and exerted their evangelism efforts, fully convinced that an existence of eternal conscious torment awaits unbelievers. This essay will examine that assertion in more detail.

The Cardinals

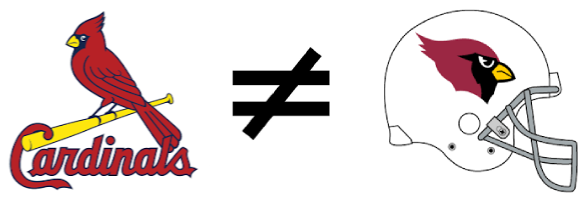

As a backdrop to this discussion, I want to present an illustration. As I write this, there are two American professional sports teams that use a mascot of ‘Cardinals’. One is the St. Louis Cardinals baseball team and the other is the Phoenix Cardinals football team.

Because I live in St. Louis, I can speak with some authority about how our baseball team is referenced. We refer to them as ‘the Cardinals’, or maybe even just ‘the Cards’. If I were talking to another St. Louis resident, there is almost no chance that I would call them “the St. Louis Cardinals” – that is, I would not append “St. Louis” to the front of that reference. If you’re in St. Louis, and you mention ‘the Cardinals’, everyone will know exactly what you are talking about.

Now, consider a scenario where the community of sports journalists in St. Louis is having an annual awards dinner. At this dinner, the keynote speaker arises and says,

Now, with this awards dinner in mind, imagine we travel 2000 years into the future, and a 41st century historian is combing through news accounts of our time, trying to understand our current culture. As part of that investigation, he stumbles upon the comments made at an awards ceremony for sports journalists. Among those comments, he comes upon the aforementioned sentence:

Now let me take this illustration in a slightly different direction and return back to the present day. What if a speaker at the St. Louis dinner actually did want to make a comment about the football team in Phoenix? Imagine he did so by using the same sentence I presented above:

I hope these illustrations make two things very clear:

John the Baptist

With those truths in hand, let’s consider first a statement of John the Baptist from Luke:

Now we, just like our assumed 41st century historian, want to know what John the Baptist intended with this statement. To do so, we must understand his audience and the context in which this statement was made.

Many in his audience would have been farmers. They dealt with chaff at every harvest. When the pile of chaff remained, they just wanted to get rid of it. They didn’t want to torment the chaff, just discard it. They knew that it would burn quickly once set on fire. Wheat chaff is light and airy, and once set on fire would almost instantly disintegrate in the flames. So, based upon their experience, any illustration of chaff in a fire would clearly communicate to them the notion of total destruction.

Additionally, as part of investigation, we should also be clear about the verb used in this statement. There are two similar verbs in the Greek language. One means “to burn”, the other means “to burn up” or “to consume”. The second verb is a stronger verb that makes it clear that the object is totally consumed. John used the stronger verb, so he unambiguously says that the chaff is consumed.

We can also note that, according to John, this chaff would be burned up with ‘unquenchable fire’. Sometimes, this Greek phrase is translated ‘a fire that will not be quenched’. How would his audience have understood this phrase? What was John trying to communicate here?

This phrase from John is almost certainly a phrase that he took from the Old Testament. Let me give just two examples of similar phrases in the Old Testament:

Below is one more example to consider. This passage does not include a form of the word ‘quench’, but it is instructive:

For these reasons, I must conclude that those who heard John’s message about chaff in an unquenchable fire would get the image of objects that are quickly consumed in the fire of God’s wrath. As John’s audience was leaving his sermon, those people most likely were thinking something like this, “I better repent, or else I will be totally burned up in the judgment day, like chaff in a fire.” Not one of them would have walked away with an image of existing forever in the upcoming fire of judgment. John’s ‘Jewish-farmer’ audience almost certainly would have understood his description of chaff in unquenchable fire as a depiction of something being totally consumed in a fire of complete destruction.

If you assert that John believed in eternal torment, then surely he earnestly tried to communicate that doctrine accurately to his audience. According to you, then, after much thought and prayer, he decided the best analogy he could use to illustrate enduring torment without end would be chaff in a fire. And what's more, he then decided that he should use the specific term 'unquenchable fire', which was use multiple times throughout the Old Testament to illustrate a fire that totally consumes that which it burns. If John expected his audience to understand eternal torment after picking those elements for his illustration, that strikes me as worse than a St. Louis sports fan expecting his audience to understand the Phoenix football team when he uses the term 'Cardinals'. It would be an epic failure of communication.

Jesus

Now let’s consider Jesus. How did he choose to express his idea of the fate that awaits unbelievers? He clearly said that they would be thrown into a fire. He clearly said that the impact of that fire would be eternal.

Along with those statements, he said that God would destroy both soul and body in hell. Yes, he said God would destroy both soul and body in hell.

According to Jesus, then, whatever happens to the body at physical death is same thing that will happen to the soul in hell. The parallel meaning is clear. When Jesus says that both soul and body will be destroyed, it certainly sounds like soul and body would cease to exist. If Jesus wanted to be clearly understood in expressing the notion of eternal torment, why would he use such words?

Also, why would he say that those who reject him will perish? I’m talking about this famous verse

Jesus spoke in Aramaic, but the book of John was written in Greek. How does one learn Greek, except by reading the Greek language? Greek students of the time would have read famous Greek authors. Few Greek authors were more famous than Plato. I suspect that most readers and writers of Greek (including our author, John) would have read and been influenced by the writings of Plato.

To be even more specific, Plato wrote a famous dialog called the Phaedo. This dialog details the discussion between Socrates and his disciples as he was waiting to be executed. The entire dialog dealt with the topic of death, and what happens to a person when they die. So, this document is especially pertinent if we want to understand a later statement that also deals with the topic of what happens at death. In the Phaedo, we read this passage [70a]:

I repeat that this was a famous document. Consider a famous document from closer to our own times, the Declaration of Independence. In that document is the phrase “the pursuit of happiness.” That phrase has entered our culture, such that when you hear the phrase “the pursuit of happiness”, you understand that the speaker is probably referring to the concept that was written by Thomas Jefferson. I suspect that this word “perish” in the Phaedo might have entered their culture in a similar way.

Given the definition of perish that is applied to the death of a human soul in the Phaedo, what do you think John intended when he chose the Greek word ‘perish’ to express the ideas of Jesus? If John wanted to express the notion of eternal existence, would he risk using a word so likely to be misunderstood by his audience?

And it’s not just words, but images as well. Consider the images in these quotes from Jesus:

Jesus used the image of weeds (tares) that are burned up in a fire to represent unbelievers at judgment day. We all know what happens to weeds in a fire – they cease to exist. Again, it would be so easy for his audience to believe that those unbelievers would cease to exist after hearing Jesus use this illustration. If Jesus wanted to express the notion of eternal existence, why in the world would he use the image of weeds in a fire?

And why would he also use the image of dried branches in a fire? These people were very familiar with vineyards in this time, and often would have witnessed what happens to branches, pruned from the vine and dried up, that are thrown into a fire. In burning the pruned branches, these grape farmers were not trying to torment them. They were just trying to get rid of them, and they knew that the best way to do that was to burn them up.

If you insist that Jesus believed in eternal torment, then he must have tried to communicate that doctrine accurately to his audience. According to you, then, after much thought and prayer, he decided to describe what happens in hell as God destroying both body and soul. According to that illustration, his audience would have understood that what happens to the soul in hell is similar to what happens to the body at physical death. And he further decided he should warn his audience against a fate he describes as 'perishing', without once using the phrase 'eternal torment' or 'eternal separation'. What's more, he decided the best analogy he could find to illustrate souls forever existing and separated from God, immortally experiencing pain without end and without hope, were the images of weeds and dried branches getting 'burned up' in a fire. If Jesus expected his audience to understand eternal torment after picking those elements for his illustration, then that once again appears to be a communication strategy worse than using the word 'Cardinals' in St. Louis to talk about the Phoenix football team. It would be an epic failure of communication.

Peter

Let’s move on to Peter. There are multiple statements from Peter that we could examine, but let me concentrate on just one. In Acts chapter three, Peter and John were going to the temple to pray. What happened next was that Peter healed a man that had been lame since birth. In response to the commotion caused by this healing, Peter gave a sermon. He clearly preached the gospel and called for repentance. According to Peter, what would happen to those that don’t repent? Here’s what he said:

In English, the phrase "utterly destroyed" seems clear enough. If we heard that an object was utterly destroyed, I suspect that most of us would conclude that the object no longer exists. But perhaps this phrase meant something different to his original audience. How would the original audience have understood that phrase?

It turns out that the original phrase probably meant something even stronger to the original audience than it does to us. In the Old Testament, on multiple occasions, God commanded the Israelites to utterly destroy certain things, sometimes an entire nation. I know this thought may be disturbing to some people, and I understand those concerns. It seems a strange command coming from a loving God. I believe there are ways to reconcile those commands with a loving God, but that is a discussion for another time. For purposes of this current discussion, there is little doubt about what this phrase would have meant to the Jews.

Let me give just one example. Below is a passage from the book of 1 Samuel. In this passage, Samuel is delivering a message to Saul from God:

Following this command, Saul did defeat the Amalekites. However, he failed to utterly destroy some of the sheep and oxen. Below is a subsequent passage, where Samuel confronts Saul about his disobedience:

When Samuel heard the sheep, it was clear to him that they had not been utterly destroyed. If you notice, Saul knows that he did not utterly destroy the animals. He says that they "spared" them. He has no doubt what "utterly destroy" means. It turns out that this disobedience cost him his position as king of Israel.

And that is just one example of this phrase "utterly destroy". I believe this same phrase occurs over 200 times in the Old Testament. This command from God occurs over and over again. When the Old Testament was translated into Greek, the word used to express the verb 'utterly destroy' is ἐξωλέθρευσα (EXOLETHREUSA). This is the exact same word used by Luke in Acts chapter 3. I suspect that Peter intentionally chose this word to convey a very specific and well-known concept to his audience. When God commanded a nation to be utterly destroyed, he was not commanding that they be imprisoned. He was not commanding that they be captured and tormented. His intention was that they would be utterly destroyed with absolutely nothing left. And that is the concept Peter applied to those souls that don't accept Christ.

It is also important to note that Peter used the word "soul" to describe the thing that will be utterly destroyed. The Greek word is ψυχη (psuche). This is the same word that appears in the book of Mark, when Jesus said, "For what does it profit a man to gain the whole world, and forfeit his soul? ". The word soul is difficult to define precisely, but clearly Jesus was referring to that part of a man which might live forever. That part of the man is exactly the part that will be utterly destroyed according to Peter.

If you want to cling to the belief that Peter believed in eternal torment, won't you at least acknowledge that Peter would try hard to communicate this to those he spoke to? Jesus asked Peter to 'feed my sheep', so surely Peter took that command seriously. Or maybe Peter didn't try that hard, but just trusted the spirit to give him the right words at the time. Regardless, the words that came out of Peter's mouth as describing the fate of those souls that reject Jesus are words that his audience would immediately recognize as expressing total destruction, with absolutely nothing left over. Peter said that souls that reject Jesus will be utterly destroyed. If he wanted to express a notion of some object persisting on throughout all eternity, then why would he make a statement that was so likely to be misunderstood by his audience? It once again sounds like a person who expects a St. Louis audience to think about footballs and Phoenix when they hear the word 'Cardinals'. How could we describe this as anything other than an epic failure of communication?

Paul

Finally, let’s consider Paul. What was it that Paul claimed would be the destiny of unbelievers? Here are some of his statements:

Paul had so many opportunities to clearly express the notion of eternal torment, but never once did he do so. Never once did he use the phrase 'eternal torment' or 'eternal separation'. In every case where this topic came up, he talked about the destruction of unbelievers. Based upon his statements, it would have been so easy for his audience to believe that unbelievers will be destroyed at the judgment day. If he truly believed in the eternal torment of unbelievers, why would he use language that was so likely to be misunderstood? I continue to come back to this illustration of using the word 'Cardinals' in St. Louis in hopes of getting your audience to think about the Phoenix Cardinals. I truly want to drive home the point that Paul failed just as badly if he wanted to express the notion of eternal torment - forever existing and yet separated from God. If that's what Paul believed, surely you recognize why I would consider his efforts to be an epic failure of communication?

Objection: Inappropriate Extrapoloation

At this point, let me address a few objections that might be raised by some. First, some might say that I’m inappropriately extrapolating from the illustrations used by these men. Some might say that the use of chaff and weeds and dried branches was not intended to illustrate the destruction of unbelievers. To make conclusions like that, they might say, is to push the analogies too far.

Certainly, errors can be made by the inappropriate application of illustrations. Illustrations typically have a central point. A good speaker will choose an illustration that clearly illustrates the central point. Errors can occur when the audience focuses on peripheral points within the illustrations and infers unwarranted conclusions.

That is not the case here. In these illustrations of both John the Baptist and Jesus, the central point was, in fact, the fate of unbelievers. Both John and Jesus were focused upon warning people to repent by illustrating what would happen if they didn’t. The destruction of the chaff and weeds and dried branches was the central point of the respective message. It is unjustified to claim that the fate of those objects was not central to the question of what happens to unbelievers.

On top of that, we must believe that these men prayed hard to find the right words to express their positions. When Jesus spoke of John the Baptist, he said this, “What did you go out into the wilderness to see? A reed shaken by the wind?“ No, John was not a reed shaken by the wind. He was not easily swayed by men. John was a formidable man, deeply dedicated to speaking the truth as he saw it. Surely, his heart ached to preach the truth. Surely, he prayed to God that he would speak the truth clearly and would find images that unambiguously expressed the truth of God.

Are you truly prepared to make that case that John and Jesus chose poor illustrations for the fate of unbelievers? If they wanted to conjure the notion of eternal existence, why not present an illustration of a rock in fire, getting red hot, but never burning up? Why not present an illustration of man getting thrown into prison, and never getting released? The fate of unbelievers was the central point in these passages, and I believe that they chose exactly those images that best illustrated what God wanted them to convey.

Objection: Selective Choice of Passages

Another objection that some might make is that I’m being very selective in the passages I’m using. They might say that other messages from these men clearly illustrate the eternal torment of unbelievers. That objection would also be mistaken.

As an example, some might raise the passages the speak of ‘weeping and gnashing of teeth’. Surely those passages illustrate eternal torment. Do they? Here are the seven passages where the phrase ‘weeping and gnashing of teeth’ is used by Jesus:

Please check them out. Not one of them mentions that this weeping and gnashing of teeth will go on forever. If you thought that, you were just projecting your own preconceived notion onto the passages.

I want to elaborate some on this phrase ‘weeping and gnashing of teeth’. I did a search in the Old Testament on the forms of the word ‘gnash’. It doesn’t appear often, and I found only one time where it appeared to reference a judgment day. In Psalm 112, we have a passage that contrasts the righteous man versus the wicked man. The righteous man is steadfast and his righteousness endures forever. His horn will be exalted in honor. About the wicked man, however, we read this:

This concept is confirmed in this passage from Luke:

One other passage is sometimes used to justify the teaching of eternal conscious torment. The parable of the rich man and Lazarus depicts the rich man being in torment after his death. Contrary to the claims of some, this parable does not teach the eternal torment of unbelievers. For one thing, it is just a parable, and scholars have found that Jesus based this parable upon one that Pharisees told at the time. Apparently, Pharisees liked to tell a parable about a poor man paying for his evil deeds in the afterlife. In telling this parable, Jesus was flipping the script on the Pharisees by having the rich man be the one in torment.

But that’s not the most significant reason to deny this teaching as applying to eternity. The most significant reason to deny the eternal impact of this parable is that Jesus says that the rich man was in Hades. I don’t claim to have a clear understanding of what happens to men immediately after they die, but apparently Hades is a place from Greek mythology that serves as a holding place for souls that have died. What is clear to me is this passage from Revelation:

Objection: The Sheep and the Goats

One final objection might be raised from the parable of the sheep and goats. In summarizing that story, Jesus says this:

But more important is the truth that a punishment that destroys a person with no hope of future resurrection is, in fact, an eternal punishment. This can best be understood by considering capital punishment. The process of killing a criminal lasts a very short time. It is not the duration of that punishment that is significant. The true punishment is the deprivation of future life.

Now, is human capital punishment eternal? We would all say no. We can imagine a criminal that truly repents while on death row, and so he will be resurrected and live with Christ for eternity. Human capital punishment is not an eternal punishment.

But what if we wanted to describe a capital punishment whose impact truly was eternal? How might we describe a punishment that totally destroys both the body and the soul, with no hope of future resurrection? Isn’t it fair to describe it as an eternal punishment? Yes, it’s very fair. When Jesus said that being thrown into the eternal fire was an eternal punishment, it is very likely that he was expressing the exact same thing that he had already expressed elsewhere – that the punishment of hell will destroy both soul and body with no hope of future resurrection. In that way, it will be a punishment of eternal impact, and therefore logically described as an eternal punishment.

A Clear Warning against Eternal Torment

Before I close, I want to consider one other question. What would it sound like if somebody truly did want to warn against eternal conscious torment? If we could know that, we could compare those statements against the statements of these men.

It turns out that we have a very good example of a warning against eternal conscious torment. Below is an example that does sound very much like a warning against eternal conscious torment. This is an excerpt from Jonathan Edwards’ sermon Sinners in the Hands of an Angry God:

Let’s compare and contrast.

As illustrated above, Edwards had multiple statements that express the same thing, but even just one of these statements would clearly express the notion. Do you see how easy it would have been for the biblical evangelists to illustrate the notion of eternal torment? They never did – not even once.

At the beginning of this essay, I presented the illustration of an awards dinner in St. Louis for local sports journalists. I asked you to consider a speaker at the dinner who expected his audience to understand a reference to “the Cardinals” as being a reference to the Phoenix Cardinals football team. I hope we all agree that such an expectation would be an epic failure of communication.

It seems to me that it would be a failure of equal proportions if these great evangelists expected their audiences to understand the notion of eternal conscious torment based upon the language that they chose to use.

Why am I asking those questions? Because if you hold a certain belief, it sure seems like they failed. I’m talking about the belief that unbelievers will suffer eternal conscious torment. If these great evangelists intended to express the notion that unbelievers are destined to suffer eternal conscious torment, they did a really poor job of expressing it.

With this essay, I will question something that you might have believed your whole life. Many Christians believe that unbelievers will be cast in hell and will exist eternally in a state that is totally devoid of God’s presence. Some have depicted this state as one of burning, or of torment, or of intense cold, or of darkness. Regardless of the specifics, though, surely any existence that is totally devoid of God’s goodness would be a terrible one.

I believe in the existence of hell, but I believe that hell will be a place of annihilation. Those thrown into hell will eventually cease to exist and will be eternally deprived of the opportunity to live in the glorious presence of God. This is what John the Baptist, Jesus, Peter and Paul taught. They made it clear.

Many will disagree with me on that point. They believe that these men went through their lives, and exerted their evangelism efforts, fully convinced that an existence of eternal conscious torment awaits unbelievers. This essay will examine that assertion in more detail.

The Cardinals

As a backdrop to this discussion, I want to present an illustration. As I write this, there are two American professional sports teams that use a mascot of ‘Cardinals’. One is the St. Louis Cardinals baseball team and the other is the Phoenix Cardinals football team.

Because I live in St. Louis, I can speak with some authority about how our baseball team is referenced. We refer to them as ‘the Cardinals’, or maybe even just ‘the Cards’. If I were talking to another St. Louis resident, there is almost no chance that I would call them “the St. Louis Cardinals” – that is, I would not append “St. Louis” to the front of that reference. If you’re in St. Louis, and you mention ‘the Cardinals’, everyone will know exactly what you are talking about.

Now, consider a scenario where the community of sports journalists in St. Louis is having an annual awards dinner. At this dinner, the keynote speaker arises and says,

- I expect the Cardinals to have great success this upcoming season.

Now, with this awards dinner in mind, imagine we travel 2000 years into the future, and a 41st century historian is combing through news accounts of our time, trying to understand our current culture. As part of that investigation, he stumbles upon the comments made at an awards ceremony for sports journalists. Among those comments, he comes upon the aforementioned sentence:

- I expect the Cardinals to have great success this upcoming season.

Now let me take this illustration in a slightly different direction and return back to the present day. What if a speaker at the St. Louis dinner actually did want to make a comment about the football team in Phoenix? Imagine he did so by using the same sentence I presented above:

- I expect the Cardinals to have great success this upcoming season.

I hope these illustrations make two things very clear:

- If we want to know what a speaker intended, it is crucial to know the context of his comments and the expectations of his audience.

- If you are a speaker and the members of your audience have a common set of expectations, you fail in your communication if you don’t consider those expectations.

John the Baptist

With those truths in hand, let’s consider first a statement of John the Baptist from Luke:

- (Luke 3:17) His winnowing fork is in His hand to thoroughly clear His threshing floor, and to gather the wheat into His barn; but He will burn up the chaff with unquenchable fire.

Now we, just like our assumed 41st century historian, want to know what John the Baptist intended with this statement. To do so, we must understand his audience and the context in which this statement was made.

Many in his audience would have been farmers. They dealt with chaff at every harvest. When the pile of chaff remained, they just wanted to get rid of it. They didn’t want to torment the chaff, just discard it. They knew that it would burn quickly once set on fire. Wheat chaff is light and airy, and once set on fire would almost instantly disintegrate in the flames. So, based upon their experience, any illustration of chaff in a fire would clearly communicate to them the notion of total destruction.

Additionally, as part of investigation, we should also be clear about the verb used in this statement. There are two similar verbs in the Greek language. One means “to burn”, the other means “to burn up” or “to consume”. The second verb is a stronger verb that makes it clear that the object is totally consumed. John used the stronger verb, so he unambiguously says that the chaff is consumed.

We can also note that, according to John, this chaff would be burned up with ‘unquenchable fire’. Sometimes, this Greek phrase is translated ‘a fire that will not be quenched’. How would his audience have understood this phrase? What was John trying to communicate here?

This phrase from John is almost certainly a phrase that he took from the Old Testament. Let me give just two examples of similar phrases in the Old Testament:

- (Jer 7:20) Therefore thus says the Lord GOD, "Behold, My anger and My wrath will be poured out on this place, on man and on beast and on the trees of the field and on the fruit of the ground; and it will burn and not be quenched."

- (Eze 20:47) and say to the forest of the Negev, 'Hear the word of the LORD: thus says the Lord GOD, "Behold, I am about to kindle a fire in you, and it will consume every green tree in you, as well as every dry tree; the blazing flame will not be quenched and the whole surface from south to north will be burned by it.

Below is one more example to consider. This passage does not include a form of the word ‘quench’, but it is instructive:

- (Amos 1:12) "So I will send fire upon Teman And it will consume the citadels of Bozrah."

For these reasons, I must conclude that those who heard John’s message about chaff in an unquenchable fire would get the image of objects that are quickly consumed in the fire of God’s wrath. As John’s audience was leaving his sermon, those people most likely were thinking something like this, “I better repent, or else I will be totally burned up in the judgment day, like chaff in a fire.” Not one of them would have walked away with an image of existing forever in the upcoming fire of judgment. John’s ‘Jewish-farmer’ audience almost certainly would have understood his description of chaff in unquenchable fire as a depiction of something being totally consumed in a fire of complete destruction.

If you assert that John believed in eternal torment, then surely he earnestly tried to communicate that doctrine accurately to his audience. According to you, then, after much thought and prayer, he decided the best analogy he could use to illustrate enduring torment without end would be chaff in a fire. And what's more, he then decided that he should use the specific term 'unquenchable fire', which was use multiple times throughout the Old Testament to illustrate a fire that totally consumes that which it burns. If John expected his audience to understand eternal torment after picking those elements for his illustration, that strikes me as worse than a St. Louis sports fan expecting his audience to understand the Phoenix football team when he uses the term 'Cardinals'. It would be an epic failure of communication.

Jesus

Now let’s consider Jesus. How did he choose to express his idea of the fate that awaits unbelievers? He clearly said that they would be thrown into a fire. He clearly said that the impact of that fire would be eternal.

Along with those statements, he said that God would destroy both soul and body in hell. Yes, he said God would destroy both soul and body in hell.

- Mat_10:28 Don’t fear those who kill the body but are not able to kill the soul; rather, fear him who is able to destroy both soul and body in hell.

According to Jesus, then, whatever happens to the body at physical death is same thing that will happen to the soul in hell. The parallel meaning is clear. When Jesus says that both soul and body will be destroyed, it certainly sounds like soul and body would cease to exist. If Jesus wanted to be clearly understood in expressing the notion of eternal torment, why would he use such words?

Also, why would he say that those who reject him will perish? I’m talking about this famous verse

- (John 3:16) For God so loved the world, that He gave His only begotten Son, that whoever believes in Him shall not perish, but have eternal life.

Jesus spoke in Aramaic, but the book of John was written in Greek. How does one learn Greek, except by reading the Greek language? Greek students of the time would have read famous Greek authors. Few Greek authors were more famous than Plato. I suspect that most readers and writers of Greek (including our author, John) would have read and been influenced by the writings of Plato.

To be even more specific, Plato wrote a famous dialog called the Phaedo. This dialog details the discussion between Socrates and his disciples as he was waiting to be executed. The entire dialog dealt with the topic of death, and what happens to a person when they die. So, this document is especially pertinent if we want to understand a later statement that also deals with the topic of what happens at death. In the Phaedo, we read this passage [70a]:

- …but in regard to the soul men are very prone to disbelief. They fear that when the soul leaves the body it no longer exists anywhere and that on the day when the man dies it is destroyed and perishes, and when it leaves the body and departs from it, straightway it flies away and is no longer anywhere, scattering like a breath or smoke.

I repeat that this was a famous document. Consider a famous document from closer to our own times, the Declaration of Independence. In that document is the phrase “the pursuit of happiness.” That phrase has entered our culture, such that when you hear the phrase “the pursuit of happiness”, you understand that the speaker is probably referring to the concept that was written by Thomas Jefferson. I suspect that this word “perish” in the Phaedo might have entered their culture in a similar way.

Given the definition of perish that is applied to the death of a human soul in the Phaedo, what do you think John intended when he chose the Greek word ‘perish’ to express the ideas of Jesus? If John wanted to express the notion of eternal existence, would he risk using a word so likely to be misunderstood by his audience?

And it’s not just words, but images as well. Consider the images in these quotes from Jesus:

- Mat 13:30 'Allow both to grow together until the harvest; and in the time of the harvest I will say to the reapers, "First gather up the tares and bind them in bundles to burn them up; but gather the wheat into my barn."'"

- Joh 15:6 "If anyone does not abide in Me, he is thrown away as a branch and dries up; and they gather them, and cast them into the fire and they are burned.

Jesus used the image of weeds (tares) that are burned up in a fire to represent unbelievers at judgment day. We all know what happens to weeds in a fire – they cease to exist. Again, it would be so easy for his audience to believe that those unbelievers would cease to exist after hearing Jesus use this illustration. If Jesus wanted to express the notion of eternal existence, why in the world would he use the image of weeds in a fire?

And why would he also use the image of dried branches in a fire? These people were very familiar with vineyards in this time, and often would have witnessed what happens to branches, pruned from the vine and dried up, that are thrown into a fire. In burning the pruned branches, these grape farmers were not trying to torment them. They were just trying to get rid of them, and they knew that the best way to do that was to burn them up.

If you insist that Jesus believed in eternal torment, then he must have tried to communicate that doctrine accurately to his audience. According to you, then, after much thought and prayer, he decided to describe what happens in hell as God destroying both body and soul. According to that illustration, his audience would have understood that what happens to the soul in hell is similar to what happens to the body at physical death. And he further decided he should warn his audience against a fate he describes as 'perishing', without once using the phrase 'eternal torment' or 'eternal separation'. What's more, he decided the best analogy he could find to illustrate souls forever existing and separated from God, immortally experiencing pain without end and without hope, were the images of weeds and dried branches getting 'burned up' in a fire. If Jesus expected his audience to understand eternal torment after picking those elements for his illustration, then that once again appears to be a communication strategy worse than using the word 'Cardinals' in St. Louis to talk about the Phoenix football team. It would be an epic failure of communication.

Peter

Let’s move on to Peter. There are multiple statements from Peter that we could examine, but let me concentrate on just one. In Acts chapter three, Peter and John were going to the temple to pray. What happened next was that Peter healed a man that had been lame since birth. In response to the commotion caused by this healing, Peter gave a sermon. He clearly preached the gospel and called for repentance. According to Peter, what would happen to those that don’t repent? Here’s what he said:

- (Acts 3:23)And it will be that every soul that does not heed that prophet shall be utterly destroyed from among the people.'

In English, the phrase "utterly destroyed" seems clear enough. If we heard that an object was utterly destroyed, I suspect that most of us would conclude that the object no longer exists. But perhaps this phrase meant something different to his original audience. How would the original audience have understood that phrase?

It turns out that the original phrase probably meant something even stronger to the original audience than it does to us. In the Old Testament, on multiple occasions, God commanded the Israelites to utterly destroy certain things, sometimes an entire nation. I know this thought may be disturbing to some people, and I understand those concerns. It seems a strange command coming from a loving God. I believe there are ways to reconcile those commands with a loving God, but that is a discussion for another time. For purposes of this current discussion, there is little doubt about what this phrase would have meant to the Jews.

Let me give just one example. Below is a passage from the book of 1 Samuel. In this passage, Samuel is delivering a message to Saul from God:

- 1Sa 15:2-3 "Thus says the LORD of hosts, 'I will punish Amalek for what he did to Israel, how he set himself against him on the way while he was coming up from Egypt. Now go and strike Amalek and utterly destroy all that he has, and do not spare him; but put to death both man and woman, child and infant, ox and sheep, camel and donkey.'"

Following this command, Saul did defeat the Amalekites. However, he failed to utterly destroy some of the sheep and oxen. Below is a subsequent passage, where Samuel confronts Saul about his disobedience:

- 1Sa 15:13-15 Samuel came to Saul, and Saul said to him, "Blessed are you of the LORD! I have carried out the command of the LORD.But Samuel said, "What then is this bleating of the sheep in my ears, and the lowing of the oxen which I hear?" Saul said, "They have brought them from the Amalekites, for the people spared the best of the sheep and oxen, to sacrifice to the LORD your God; but the rest we have utterly destroyed."

When Samuel heard the sheep, it was clear to him that they had not been utterly destroyed. If you notice, Saul knows that he did not utterly destroy the animals. He says that they "spared" them. He has no doubt what "utterly destroy" means. It turns out that this disobedience cost him his position as king of Israel.

And that is just one example of this phrase "utterly destroy". I believe this same phrase occurs over 200 times in the Old Testament. This command from God occurs over and over again. When the Old Testament was translated into Greek, the word used to express the verb 'utterly destroy' is ἐξωλέθρευσα (EXOLETHREUSA). This is the exact same word used by Luke in Acts chapter 3. I suspect that Peter intentionally chose this word to convey a very specific and well-known concept to his audience. When God commanded a nation to be utterly destroyed, he was not commanding that they be imprisoned. He was not commanding that they be captured and tormented. His intention was that they would be utterly destroyed with absolutely nothing left. And that is the concept Peter applied to those souls that don't accept Christ.

It is also important to note that Peter used the word "soul" to describe the thing that will be utterly destroyed. The Greek word is ψυχη (psuche). This is the same word that appears in the book of Mark, when Jesus said, "For what does it profit a man to gain the whole world, and forfeit his soul? ". The word soul is difficult to define precisely, but clearly Jesus was referring to that part of a man which might live forever. That part of the man is exactly the part that will be utterly destroyed according to Peter.

If you want to cling to the belief that Peter believed in eternal torment, won't you at least acknowledge that Peter would try hard to communicate this to those he spoke to? Jesus asked Peter to 'feed my sheep', so surely Peter took that command seriously. Or maybe Peter didn't try that hard, but just trusted the spirit to give him the right words at the time. Regardless, the words that came out of Peter's mouth as describing the fate of those souls that reject Jesus are words that his audience would immediately recognize as expressing total destruction, with absolutely nothing left over. Peter said that souls that reject Jesus will be utterly destroyed. If he wanted to express a notion of some object persisting on throughout all eternity, then why would he make a statement that was so likely to be misunderstood by his audience? It once again sounds like a person who expects a St. Louis audience to think about footballs and Phoenix when they hear the word 'Cardinals'. How could we describe this as anything other than an epic failure of communication?

Paul

Finally, let’s consider Paul. What was it that Paul claimed would be the destiny of unbelievers? Here are some of his statements:

- What if God, although willing to demonstrate His wrath and to make His power known, endured with much patience vessels of wrath prepared for destruction?

- In no way alarmed by your opponents—which is a sign of destruction for them, but of salvation for you, and that too, from God.

- For many walk, of whom I often told you, and now tell you even weeping, that they are enemies of the cross of Christ, whose end is destruction

- This will take place at the revelation of the Lord Jesus from heaven with his powerful angels, when he takes vengeance with flaming fire on those who don’t know God and on those who don’t obey the gospel of our Lord Jesus. They will pay the penalty of eternal destruction from the Lord’s presence and from his glorious strength (CSB)

- But those who want to get rich fall into temptation and a snare and many foolish and harmful desires which plunge men into ruin and destruction.

Paul had so many opportunities to clearly express the notion of eternal torment, but never once did he do so. Never once did he use the phrase 'eternal torment' or 'eternal separation'. In every case where this topic came up, he talked about the destruction of unbelievers. Based upon his statements, it would have been so easy for his audience to believe that unbelievers will be destroyed at the judgment day. If he truly believed in the eternal torment of unbelievers, why would he use language that was so likely to be misunderstood? I continue to come back to this illustration of using the word 'Cardinals' in St. Louis in hopes of getting your audience to think about the Phoenix Cardinals. I truly want to drive home the point that Paul failed just as badly if he wanted to express the notion of eternal torment - forever existing and yet separated from God. If that's what Paul believed, surely you recognize why I would consider his efforts to be an epic failure of communication?

Objection: Inappropriate Extrapoloation

At this point, let me address a few objections that might be raised by some. First, some might say that I’m inappropriately extrapolating from the illustrations used by these men. Some might say that the use of chaff and weeds and dried branches was not intended to illustrate the destruction of unbelievers. To make conclusions like that, they might say, is to push the analogies too far.

Certainly, errors can be made by the inappropriate application of illustrations. Illustrations typically have a central point. A good speaker will choose an illustration that clearly illustrates the central point. Errors can occur when the audience focuses on peripheral points within the illustrations and infers unwarranted conclusions.

That is not the case here. In these illustrations of both John the Baptist and Jesus, the central point was, in fact, the fate of unbelievers. Both John and Jesus were focused upon warning people to repent by illustrating what would happen if they didn’t. The destruction of the chaff and weeds and dried branches was the central point of the respective message. It is unjustified to claim that the fate of those objects was not central to the question of what happens to unbelievers.

On top of that, we must believe that these men prayed hard to find the right words to express their positions. When Jesus spoke of John the Baptist, he said this, “What did you go out into the wilderness to see? A reed shaken by the wind?“ No, John was not a reed shaken by the wind. He was not easily swayed by men. John was a formidable man, deeply dedicated to speaking the truth as he saw it. Surely, his heart ached to preach the truth. Surely, he prayed to God that he would speak the truth clearly and would find images that unambiguously expressed the truth of God.

Are you truly prepared to make that case that John and Jesus chose poor illustrations for the fate of unbelievers? If they wanted to conjure the notion of eternal existence, why not present an illustration of a rock in fire, getting red hot, but never burning up? Why not present an illustration of man getting thrown into prison, and never getting released? The fate of unbelievers was the central point in these passages, and I believe that they chose exactly those images that best illustrated what God wanted them to convey.

Objection: Selective Choice of Passages

Another objection that some might make is that I’m being very selective in the passages I’m using. They might say that other messages from these men clearly illustrate the eternal torment of unbelievers. That objection would also be mistaken.

As an example, some might raise the passages the speak of ‘weeping and gnashing of teeth’. Surely those passages illustrate eternal torment. Do they? Here are the seven passages where the phrase ‘weeping and gnashing of teeth’ is used by Jesus:

- Matthew 8:12

- Matthew 13:42

- Matthew 13:49

- Matthew 22:13

- Matthew 24:51

- Matthew 35:30

- Luke 13:28

Please check them out. Not one of them mentions that this weeping and gnashing of teeth will go on forever. If you thought that, you were just projecting your own preconceived notion onto the passages.

I want to elaborate some on this phrase ‘weeping and gnashing of teeth’. I did a search in the Old Testament on the forms of the word ‘gnash’. It doesn’t appear often, and I found only one time where it appeared to reference a judgment day. In Psalm 112, we have a passage that contrasts the righteous man versus the wicked man. The righteous man is steadfast and his righteousness endures forever. His horn will be exalted in honor. About the wicked man, however, we read this:

- (Ps 112:10) The wicked will see it and be vexed, He will gnash his teeth and melt away; The desire of the wicked will perish.

This concept is confirmed in this passage from Luke:

- (Luke 13:28) In that place there will be weeping and gnashing of teeth when you see Abraham and Isaac and Jacob and all the prophets in the kingdom of God, but yourselves being thrown out.

One other passage is sometimes used to justify the teaching of eternal conscious torment. The parable of the rich man and Lazarus depicts the rich man being in torment after his death. Contrary to the claims of some, this parable does not teach the eternal torment of unbelievers. For one thing, it is just a parable, and scholars have found that Jesus based this parable upon one that Pharisees told at the time. Apparently, Pharisees liked to tell a parable about a poor man paying for his evil deeds in the afterlife. In telling this parable, Jesus was flipping the script on the Pharisees by having the rich man be the one in torment.

But that’s not the most significant reason to deny this teaching as applying to eternity. The most significant reason to deny the eternal impact of this parable is that Jesus says that the rich man was in Hades. I don’t claim to have a clear understanding of what happens to men immediately after they die, but apparently Hades is a place from Greek mythology that serves as a holding place for souls that have died. What is clear to me is this passage from Revelation:

- (Rev 20:13-14) And the sea gave up the dead which were in it, and death and Hades gave up the dead which were in them; and they were judged, every one of them according to their deeds. Then death and Hades were thrown into the lake of fire. This is the second death, the lake of fire.

Objection: The Sheep and the Goats

One final objection might be raised from the parable of the sheep and goats. In summarizing that story, Jesus says this:

- (Mat_25:46) "These will go away into eternal punishment, but the righteous into eternal life."

But more important is the truth that a punishment that destroys a person with no hope of future resurrection is, in fact, an eternal punishment. This can best be understood by considering capital punishment. The process of killing a criminal lasts a very short time. It is not the duration of that punishment that is significant. The true punishment is the deprivation of future life.

Now, is human capital punishment eternal? We would all say no. We can imagine a criminal that truly repents while on death row, and so he will be resurrected and live with Christ for eternity. Human capital punishment is not an eternal punishment.

But what if we wanted to describe a capital punishment whose impact truly was eternal? How might we describe a punishment that totally destroys both the body and the soul, with no hope of future resurrection? Isn’t it fair to describe it as an eternal punishment? Yes, it’s very fair. When Jesus said that being thrown into the eternal fire was an eternal punishment, it is very likely that he was expressing the exact same thing that he had already expressed elsewhere – that the punishment of hell will destroy both soul and body with no hope of future resurrection. In that way, it will be a punishment of eternal impact, and therefore logically described as an eternal punishment.

A Clear Warning against Eternal Torment

Before I close, I want to consider one other question. What would it sound like if somebody truly did want to warn against eternal conscious torment? If we could know that, we could compare those statements against the statements of these men.

It turns out that we have a very good example of a warning against eternal conscious torment. Below is an example that does sound very much like a warning against eternal conscious torment. This is an excerpt from Jonathan Edwards’ sermon Sinners in the Hands of an Angry God:

- 'Tis everlasting Wrath. It would be dreadful to suffer this Fierceness and Wrath of Almighty God one Moment; but you must suffer it to all Eternity: there will be no End to this exquisite horrible Misery: When you look forward, you shall see a long Forever, a boundless Duration before you, which will swallow up your Thoughts, and amaze your Soul; and you will absolutely despair of ever having any Deliverance, any End, any Mitigation, any Rest at all; you will know certainly that you must wear out long Ages, Millions of Millions of Ages, in wrestling and conflicting with this almighty merciless Vengeance; and then when you have so done, when so many Ages have actually been spent by you in this Manner, you will know that all is but a Point to what remains. So that our Punishment will indeed be infinite. Oh who can express what the State of a Soul in such Circumstances is! All that we can possibly say about it, gives but a very feeble faint Representation of it; 'tis inexpressible and inconceivable: for who knows the Power of God’s Anger?

Let’s compare and contrast.

- Jonathan Edwards said, “there will be no End to this exquisite horrible Misery”.

- John the Baptist said, “they will be like chaff in the fire”

- Jonathan Edwards said, “when you look forward, you will see a long forever, a boundless duration”

- Jesus said, “God will destroy both soul and body in hell…they will perish…like weeds in a fire…like dried branches in a fire”

- Jonathan Edwards said, “you will know certainly that you must wear out long Ages, Millions of Millions of Ages, in wrestling and conflicting with this almighty merciless Vengeance”

- Peter said, “You will be utterly destroyed.”

- Jonathan Edwards said, “when so many Ages have actually been spent by you in this Manner, you will know that all is but a Point to what remains”

- Paul said, over and over again, “You will be destroyed”

As illustrated above, Edwards had multiple statements that express the same thing, but even just one of these statements would clearly express the notion. Do you see how easy it would have been for the biblical evangelists to illustrate the notion of eternal torment? They never did – not even once.

At the beginning of this essay, I presented the illustration of an awards dinner in St. Louis for local sports journalists. I asked you to consider a speaker at the dinner who expected his audience to understand a reference to “the Cardinals” as being a reference to the Phoenix Cardinals football team. I hope we all agree that such an expectation would be an epic failure of communication.

It seems to me that it would be a failure of equal proportions if these great evangelists expected their audiences to understand the notion of eternal conscious torment based upon the language that they chose to use.